9

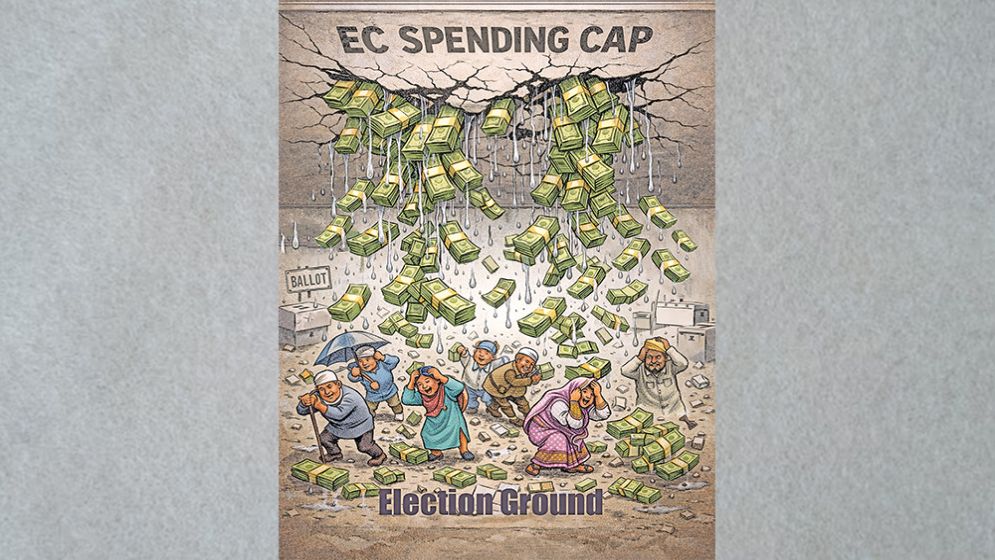

As election campaigning reaches fever pitch across the country, vast sums of money – much of it unaccounted for – are flooding the political field, casting fresh doubt on the effectiveness of campaign spending limits and the integrity of the electoral process.

With polling day approaching, evidence suggests that actual expenditure is far exceeding the ceilings set by the Election Commission, fuelled largely by a surge in cash withdrawals from the banking system.

Candidates are campaigning relentlessly, day and night, with posters, processions, rallies and logistics demanding heavy financial outlays. While rhetoric and promises dominate public platforms, money remains a decisive factor in determining electoral reach and visibility. As spending accelerates, the true sources and scale of campaign funds remain largely opaque.

The Election Commission (EC) has set a ceiling on campaign expenditure. For national parliamentary elections, the allowable spending limit is Tk10 per voter. Gazipur-2 has the highest number of voters – 804,333 – allowing candidates there to spend a maximum of Tk8,043,330.

The Election Commission (EC) has set a ceiling on campaign expenditure. For national parliamentary elections, the allowable spending limit is Tk10 per voter. Gazipur-2 has the highest number of voters – 804,333 – allowing candidates there to spend a maximum of Tk8,043,330.

At the other end of the scale, Jhalokathi-1 has the lowest number of voters among the 300 constituencies, with 228,431 voters. Candidates there can spend up to Tk25 lakh, which works out at Tk22.84 per voter.

Dhaka-19 has the second-highest voter base, with 747,070 voters, permitting a maximum expenditure of Tk7,470,700.

In previous elections, although the per-voter spending limit was set at Tk10, no candidate was allowed to spend more than Tk25 lakh in total. That rule has been revised this time. In the 13th National Parliamentary Election, candidates may spend either Tk25 lakh or Tk10 per voter – whichever amount is higher.

Speaking on election expenditure, Election Commissioner Brig Gen (retd) Abul Fazal Md Sanaullah said candidates are allowed to spend up to Tk10 per voter or a maximum of Tk25 lakh, whichever is higher. Under Article 44 of the Representation of the People Order (RPO), per-voter election expenditure has been fixed at Tk10.

However, judging by the scale and nature of campaigning across the country, it is not difficult to conclude that these limits are being widely ignored.

Campaign spending far exceeds the prescribed ceilings.

Several candidates have alleged that black money is being openly distributed. Data from Bangladesh Bank appear to support these claims.

There has been a surge in cash withdrawals from banks to finance election campaigns. Over the past two months – December and January – cash circulation outside the banking system has increased by nearly Tk41,000 crore.

Bangladesh Bank Executive Director and spokesperson Arif Hossain Khan confirmed this to the media, saying withdrawals have risen sharply due largely to election-related expenses.

Bangladesh Bank publishes monthly data by subtracting bank deposits from total currency in circulation. In November last year, cash outside banks stood at Tk269,018 crore.

Bangladesh Bank publishes monthly data by subtracting bank deposits from total currency in circulation. In November last year, cash outside banks stood at Tk269,018 crore.

By January this year, the figure had climbed to Tk310,000 crore – an increase of Tk40,982 crore in just two months.

From July last year, cash outside banks had been on a downward trend. It stood at Tk287,294 crore in July, fell to Tk276,494 crore in August, Tk274,724 crore in September and Tk270,449 crore in October. The decline continued until November, before reversing due to election spending.

To curb the influence of black money, Bangladesh Bank and the Election Commission have taken several steps.

From 11 January, the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit (BFIU) strengthened monitoring of cash deposits and withdrawals.

Under its directive, any cash transaction of Tk10 lakh or more – whether deposit or withdrawal, single or multiple transactions within a day, including online and ATM transactions – must be reported through a Cash Transaction Report (CTR).

Until further notice, CTRs must be submitted weekly within three working days of the following week. Failure to submit reports on time, or providing incorrect or false information, will invite action under the Money Laundering Prevention Act.

Meanwhile, ahead of the election, mobile financial services (MFS) have been restricted. Users of bKash, Rocket, Nagad and other platforms will be able to transact a maximum of Tk10,000 per day, with each transaction capped at Tk1,000. Person-to-person transfers via internet banking will also be suspended. These restrictions will remain in force from 8 to 13 February.

These measures are aimed at preventing the misuse of money to influence voters and were taken by the BFIU at the request of the Election Commission.

However, experts believe that while such initiatives may reduce the flow of black money to some extent, they are unlikely to eliminate it altogether.

Those who treat politics as a business will continue to use illicit funds by any means necessary to secure victory.

Political analysts argue that some candidates enter elections purely to serve personal interests. They see politics as a shortcut to wealth, abusing power once elected. Public service is neither their motive nor their concern. Such practices have criminalised politics and entrenched corruption.

Candidates invest heavily in elections, use black money to sway voters, and once in office, recover their costs many times over through large-scale looting.

Unless this vicious cycle is broken, the country will remain trapped in corruption and democracy will struggle to take root. Voters must raise their voices against the use of black money, and the Election Commission must take a far firmer stance.